The Books That Kept My Houseplants Alive

I’m going to buy another money tree and not kill it this time, I thought to myself last year while reading articles about the pandemic houseplant craze. I wanted to participate in cute trends like reading books based on your favorite houseplant, but the only time I had tried to keep a plant alive, I failed miserably. Before the start of the pandemic, my mother gifted me a money tree after I got my first full-time job, a family tradition. My younger sister often sends pictures of hers in group texts: it’s repotted during growing season, majestic and sprouting new leaves. I was excited to get mine but took my mother too literally when she said it didn’t need much water. She walked into my office a few months later, stopping short in front of my window. Wrenching her eyes away from my plant’s leafless, light-brown stalks, she turned towards me—appalled. “You killed it,” she said.

“I thought I wasn’t supposed to give it much water,” I responded. She picked up the pot and handed it to me.

“Drench it with water,” she instructed. “Maybe it’ll come back.”

There was no hope in her voice.

When my new money tree arrived in December 2020, I downloaded Planta, the go-to app for household plant care and management. When the app told me the plant needed “bright indirect light,” I placed it to the side of a window in my room, far enough back that it seemed the light hit it in an “indirect” way. I watered and fertilized my money tree as I received Planta’s alerts to do so and was pleased with myself until, a few months later, I noticed the trunks were shriveling up. I pressed my fingers into them. They were mushy to the touch. I panicked and frantically Googled “mushy money tree,” learning that I overwatered this time. I spread trash bags across the floor and scraped the rotten roots away, following step-by-step directions on YouTube. After I was done, there were only a few short, white roots left on two of the stalks. I doubted the plant would survive, but I repotted it anyway and wondered why a plant care app I paid for led me astray.

What does bright indirect light even mean, I thought to myself, googling “best houseplant care books.” I needed more than the step-by-step instructions that Planta or basic care guides could offer—I needed the whys beyond the obvious hows of plant care.

Thanks to these authors, I now own more than thirty plants—and that money tree I bought in December is still alive.

The New Plant Parent, by Darryl Cheng

The first book I read, when my money tree was still in need of emergency care, was Darryl Cheng’s The New Plant Parent. As opposed to dispensing “tips and tricks” that are focused on identifying and solving plant problems, Cheng argues that plant parents must foster a deep understanding of how plants thrive through knowledge and personal observation. In modeling this kind of relationship to plant care, The New Plant Parent taught me my most crucial lesson—plants eat light. I remember learning this in grade-school biology, I thought, embarrassed but grateful for the reminder. Based on the amount of light they get, Cheng explains, plants are either starving or satisfied. To know the difference, “be the plant!” he writes. Position yourself so you can see what your plant sees. Can your plant see the sun? If so, that’s direct light, and most plants can tolerate about 3-4 hours of it. Can your plant see the sky but the sun itself is obscured by buildings, screens, or sheer curtains? That’s bright-indirect light, and most plants prefer it. Does your plant have a constricted view of the sky, at best? That’s low light, and a few plants tolerate it—but none thrive in it. Cheng sums up his advice as follows: “Only some plants need to see as much sun as possible, but all plants would benefit from seeing as much daytime sky as possible.” Cheng explains how the amount of light a plant gets is inextricable from how much water it needs—the reason my plant app failed me. “A growing plant in good light is a thirsty plant,” he writes, so it follows that your plant will need different amounts of water depending on the month, not just the season.

After I read the first few chapters of The New Plant Parent, I realized that caring for plants isn’t intuitive because they’re meant to be outside. The more I learned about the ways plants exist in their natural habitats, and how to observe them existing in my home’s growing conditions, the better I began to care for my new money tree. I named her Cathy and moved her to a south-facing windowsill that bathed her in bright-indirect light. I put up sheer curtains after realizing she was seeing a little too much direct sunlight. I began to test the soil with my finger before watering and bought a good humidifier, another of Cheng’s recommendations. I also pulled some takeout chopsticks out of my junk drawer to aerate her soil, allowing “air and water to more evenly penetrate,” as Cheng directs. After a few weeks, Cathy’s stalks started producing tiny, five leaf parachute-like blooms. Then I began to accrue more plants. My daughter named our new peperomia plant “pepperoni” in a stroke of creative genius. Pepperoni now sits beside my neon-green pothos, LL, who recently began to trail. Rose, my ruby rubber plant, tips more and more to the right with each new leaf, asking me to repot her.

How to Make a Plant Love You: Cultivate Green Space in Your Home and Heart, by Summer Rayne Oakes

The next book in my lineup, Summer Rayne Oakes’s How to Make a Plant Love You: Cultivate Green Space in Your Home and Heart, repeats much of Cheng’s advice but offers larger meditations on what plants have to offer. For Oakes, our relationship to plants is reciprocal. When you care for them, they’ll care for you—“cleaning your air, calming your mind, and literally tapping into your ancient, biological need to feel connected to nature.” Her detailed descriptions of the purpose of chlorophyll (“to absorb all visible light wavelengths”), for example, conclude in statements like, plants are “slow, quiet, and most of all complex creatures”—we must “match their dispositions” when we can. Through personal testimonies sprinkled throughout the book, her own and others’, Oakes argues that caring for plants offers mental health benefits in a very-online world, one filled with “curated, unrealistic imagery” that increases levels of anxiety and depression symptoms. Oakes spends thirty minutes a day tending to her plants, longer on Sundays, and says this ritual of care is meditative while helping her keep track of and observe positive or negative changes in her plants. Surviving is not thriving, I remember, while reading Oakes—whether she is talking about plants or people.

Following Oakes’s example, I began to spend a few hours a week with my plants, watering, pruning, and wiping down their waxy leaves. (I learned from Cheng they absorb more light when clean.) I paid more attention: I cupped my palms under new variegated leaves and stood on my tiptoes to admire new growth. It’s clear that my plants adapt to their surroundings, the way they crawl up moss poles, cascade down bookshelves, and twist their stems towards light. I slow down while caring for them and, as Oakes promises, begin to “match their dispositions” more and more each day.

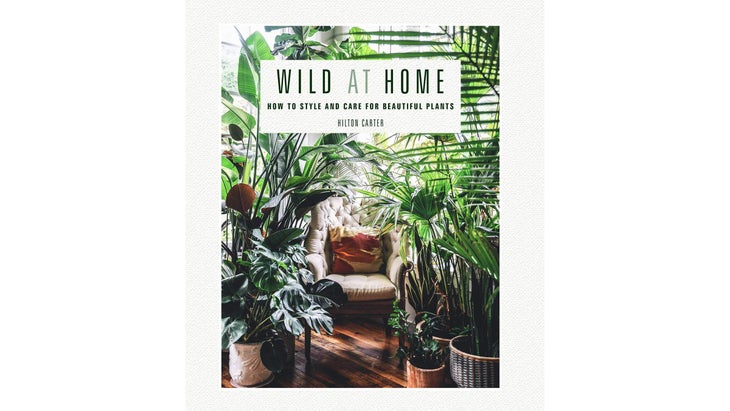

Wild At Home: How to Style and Care for Beautiful Plants, by Hilton Carter

This kind of reverence for plants also pervades Hilton Carter’s Wild At Home: How to Style and Care for Beautiful Plants. In his introduction, Carter gushes over the beauty that plants like Frank, his fiddle-leaf fig, bring to our homes, but balances his attention to the aesthetics of houseplants with advice about attending to their needs. Find a statement plant, Carter advises readers, one that has the wow factor, while also respecting that your home might not offer the conditions certain plants need, no matter how perfect they look in the space. Only after Carter outlines plant care basics does he offer styling tips, telling us to consider layers, grouping, and creating levels. When discussing planters, Carter exclaims, “You can’t just place a naked plant in your home. Have some humanity, dammit!” These asides are not just warm and hilarious, but work to remind readers constantly that a beautiful plant is a thriving plant. Carter taught me that I’m not doing plants any grand favors by bringing them inside and taking pictures of them for my Instagram page until they die. I laughed out loud when Carter described loving Little Shop of Horrors as a child, because, according to him, there is “something so interesting about the care the store clerk, Seymour, gave his plant from outer space, even going as far as feeding it his own blood… I’m not suggesting you do this for your plants.”

I wouldn’t be surprised if Carter did, honestly—if that’s what his plants needed. Carter’s focus on aesthetics doesn’t mean he sees plants as home furnishings. Quite the opposite. His appreciation for plants fuels his desire to care for them, to nurture their growth, and to show them off as the majestic beings they are. Now, when I walk into my office, I see a pair of snake plants dressed up in turquoise pots, as per Carter’s advice, positioned in the same tiny window—thriving in the space and, consequently, Instagram ready. Their dark green leaves twist upwards, rimmed in yellow. They’re gorgeous, healthy statement plants, reminding me of how far I’ve come.

I’m proud of the plant owner I am now. Thanks to these authors, my townhouse is home to thirty plus plants. When I pass by them, I pick up the pots to see how light they are, poking the dirt with chopsticks to see how much dirt comes away, to see if they need water as opposed to waiting for an alert from Planta. I notice when my purple waffle plant, Kiki, and peace lily, Pema, start to droop and then watch them perk back up moments after I water thoroughly, until I see water drip out of the nursery pots, wiping up the excess with an old cloth. I make sure my windows are clean for the first time in my life, so light can get to my plants. I go to a local nursery to buy potting soil that includes seaweed and other natural fertilizers, propagate my bromeliads, and encourage new plant parents in my workplace, asking permission to lightly grab the leaves of their new plants as I talk to them about the best way to care for them. I observe, I notice, I discover.

These books have conveyed what step-by-step instructions could not: that a relationship with plants built on love, care, and respect—as opposed to one grounded in simply keeping them alive—is at the heart of bringing the outdoors inside. I’m still not as steady, efficient, or persistent as my plants, but in keeping them alive I get a little bit closer.

The post The Books That Kept My Houseplants Alive appeared first on Outside Online.